On 30 January 2023 Noel Pearson addressed the Catholic Education Canberra-Goulburn System Day at the Canberra Convention Centre. Below is the transcript of that speech.

Good morning, everyone. I am so privileged to have been invited to join you at the System Day. I am very passionate about what you are all on about.

The first thing I want to do is acknowledge the Ngunnawal traditional owners of the land; I bring greetings from Cape York Peninsula. I want to acknowledge Ross Fox and the Catalyst team and Arch-Diocese and again thank you very much for this great privilege.

We have been on the same journey for quite a bit longer than you guys; about 15 years. You have made more progress in three that we have in 15.

Our challenge are schools with 30 per cent of the children who have been tested at the lowest level of IQ: 70. The Royal Flying Doctors found that another 40 per cent were not much above that. So we deal with children who are the children of severe trauma, alcoholism and communities that are in tragic ruin. The difficulty of working with children like that is vast. We have to do so in schools where the average length of teacher tenure is about three years and five years for principals. So the tremendous turnover of the teaching faculty whom we have to teach from day one our pedagogy that they haven’t learnt at their universities.

They learn on the job with us and when they are good, they go. So we are producing a great benefits for the schools of the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast. I would prefer that privileged schools in the city adopted the right pedagogy and sent their teachers out to us after they have developed, rather than having first year students trying to effect student learning without having been taught by their respective universities.

Ours is an uphill battle. There is also a class problem, of all of the ideas and all of the theories that I read; conservative, liberal, Marxist, Karl Marxist’s idea of the class society and the ideologies that produce and maintain those structures of inequality, structures of stratification, is the most powerful. The most saliant idea I found in my 30 years of social change combat, the most powerful idea is the idea of the camera obscura that Marx talked about. Essentially that the real image of the world is inverted in our eyes, we think we see the world right side up, but it is in fact the opposite and I see this every day; I’ve seen it every day for 32 years.

What we think are snakes are in fact ladders; what we think are ladders are in fact snakes. My rough rule of thumb when it comes to deciding what the correct policy is, is to do approximately opposite to what progressive thinking says we should do. Across the whole field: criminal justice, education, health, welfare reform, economic development. Do approximately opposite to what progressive thinking says you should do and you will get it about right. Is it any wonder that the pedagogy we believe is effective, that is underpinned by the science of learning and the science of reading, is cast as a conservative pedagogy?

Why have Direct Instruction and Explicit Instruction so steadfastly been objected to for 50 years other than the fact that it’s been characterised as traditional and conservative and punitive? Do you think this is just an accident? That poor and disadvantaged children are denied the ability to learn, read effectively and efficiently if taught through explicit and direct methods? Why would you deny a child that in favour of an ideological position against it? Other than the fact that, that is how the world works, and that is how the world works for the most disadvantaged kids in society. We in the middle class prescribe snakes rather than ladders; we present the snakes as if they are ladders, but it is completely the opposite.

This is my 32nd year of fighting for land rights; we are about 95 per cent through our journey in Cape York Peninsula. This is my 22nd year of welfare reform and economic change, and I’m about 10 per cent through my journey. And this is 22 years of thinking about education and objecting year in year out to the delivery of failure to our children, and I’m about 10 per cent through that challenge. I’m 22 years into the journey for constitutional recognition and we are about 95 per cent there. I will need your vote in October.

But of all of these hard journeys, I’m going to tell you that this education one is the thing that sickens me the most. Because I have seen so many children over 30 years fail to reach their potential. We have a juvenile justice crisis in this country and you know where it starts? It starts with the failure to read, occasioned by the failure to teach and a steadfast refusal for systems and educators to change and see the evidence.

Every year we spend stuffing around and failing to see the evidence for what it is. We fail children. We destroy lives. Yes, the middle-class kids do alright, they get through, they go to university. But it’s the kids I’m concerned about, the kids of the underclass, the kids who are disadvantaged. Every year we waste – stuffing around and failing to see 50 years of evidence about what works in the teaching of reading and in learning generally – are lives lost. What do you think is going on in Alice Springs? That’s the product of failed learning, which is the consequence of failed teaching in the communities from which those kids come. And there is no solution in sight. I’m envious of Catalyst.

This is me in Year 7 at Hope Vale State Primary School; that heart is from my father’s butcher shop. It is the only photo I have of my school days. We returned that heart to the shop to be sold again. I can report on my father; he’s long been dead.

Catalyst is the most important development in Australian school education. It is absolutely the most important development. You guys hold the hope for the country because it’s a complete system reform approach; something we’ve never had. No system in Australia has grasped school reform like you guys are doing now. I think you’re going to be a beacon for the rest of the country. It’s completely analogous to districts and regions and other subsystems that need to follow your lead and we’ll follow your lead in the years to come.

Ross’s injunction that you maintain a consistent course is absolutely critical. I’ve seen green shoots rise out of the desert for goodness sake and there’s so much excitement and hope when you see that. You can see that effective instruction can start those shoots of hope and learning but then another person comes along and he’s got a different idea; he wants to go back to inquiry learning, or some bureaucrat in the regional office has an antipathy to direct instruction and everything is torn down. Cycles of green shoots that are then destroyed.

The most important thing happening in school education is happening in this diocese. We started a long time ago; we wasted our time. I can at least say that we at least gave the other mob a good hearing, as much of the time as we wasted, we gave the other mob a good hearing with Alan Luke’s new basics, productive pedagogies, 21st century skills, multiliteracies, rich tasks, new rather than the old basics, Vygotsky, Dewey, Friere, Ted Sizer, we went through all of that and then we became apostate.

We became apostate because we met Kevin Wheldall from Multilit. We were cognisant of the reading wars in the early part of the 2000s; we saw the outcome of Ken Rowe’s National Reading Inquiry. I went to Kevin and said, ‘I want Multilit in Cape York. I’ve got a little school that I think I can sneak the program into, with 50 kids.’ So we set up a tutorial room and it was fantastic. I could see the kids learning in front of me. But it was a tutorial room on the side of the school and our question was: shouldn’t that teaching be happening in those class rooms? We didn’t just want a remedial program, we wanted the thing happening in the main classroom. At that time Multilit didn’t have an approach on that. We had a try for a year in 2006, but it was two cooks in the kitchen; us trying to do Multilit and the other mob doing God knows what.

New basics was a failure, but I learnt so much from Kevin Wheldall. Effective instruction is effective instruction is effective instruction. That’s where I learnt the equivalent to Bill Clinton’s insight that ‘It’s the instruction, stupid.’ I don’t mean to offend you by saying that, but I’m just saying how fundamental instruction is to every relationship. Yes it’s the pastoral care, yes it’s the love, yes it’s the dedication, yes it’s everything, but without effective instruction it’s nothing. My most effective teacher in primary school drilled us – I can’t remember her name – but she was my most effective teacher, I now realise.

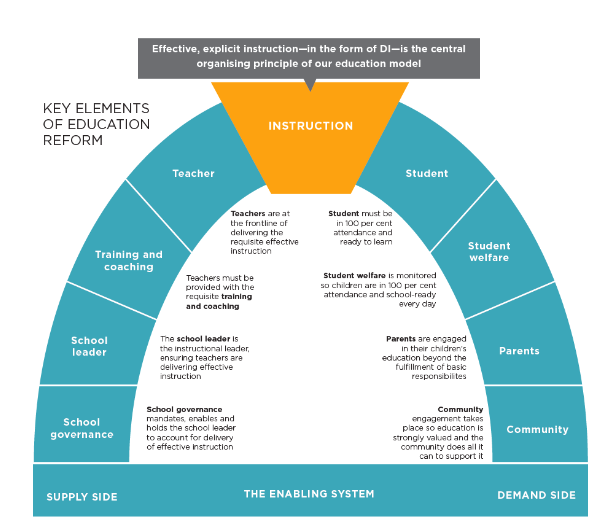

The keystone to school reform is effective instruction and that was made clear by the McKinsey report in 2007 with three things: right teachers in the place, effective instruction and every child benefiting. That was the evidence from the 2007 McKinsey report. It’s kind of the nose on your face. The teacher, the instruction, every child. That is our logo for Good to Great Schools Australia: Great teachers. Effective instruction. Every child.

This our model of the school. What we call the supply side elements, good school governance, good school leadership, training and coaching for the teachers and of course at the apex is that relationship between the teacher and the student. Key to that relationship is effective instruction. On the demand side is a community that demands better results for their children, parents that support and back their children, the welfare of the students, there is a focus on the welfare; get them ready. The first things I did – I dared not enter the classroom in 2000 – but what we did was work on the demand side; get the kids to the school, get the parents and the families to put money aside for the kids. A small community of 50 kids and they put a million dollars into trust accounts for their children out of their welfare payments. An average of $10,000 per child, to pay for books, to pay for excursions, to pay for graduation gowns when they finish high school. Get the material support for the families together and these trust accounts have been going for 15 years.

And of course, the ready student. What we lack compared to you guys is the bottom. We don’t have an enabling system, we don’t have a system that says: ‘This is the approach, this has got to be maintained, we will make sure that the right teachers are in place, that they are supported with training and coaching and all of the professional and industrial support they need.’ We don’t have the enabling system; we have a public system that is completely indifferent to what happens to the kids.

By the way, I spoke to Catholic educators 10 years ago about the same content today, urging the same thing in a conference in Broome. It was indifference, those Catholic schools have wasted 10 years, diverted by Marie Clay. Head so deep in reading recovery you couldn’t convince them of anything. Just think of all the wasted lives in those 10 years. We can’t muck around, I don’t need to tell you that, Ross is telling you that. But every year we waste on the wrong thinking about what needs to be done, we are wasting lives, wasting futures.

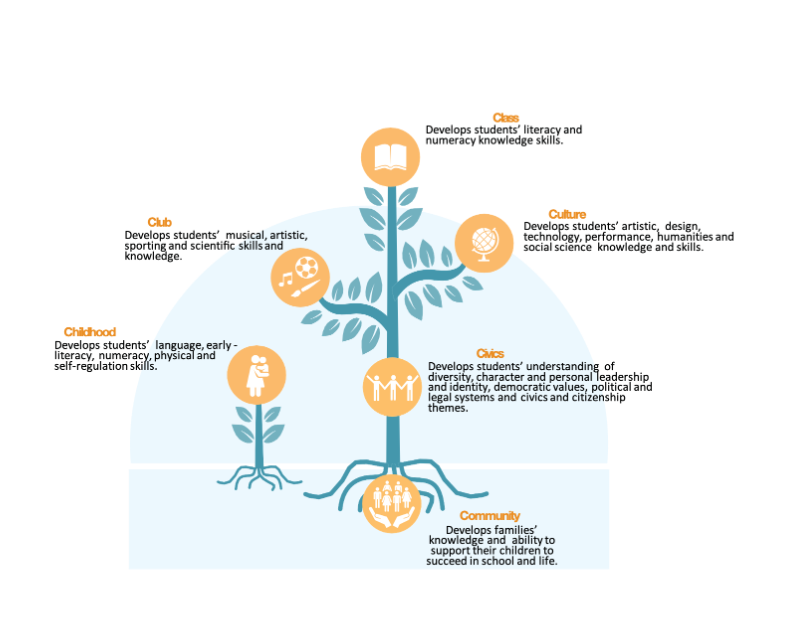

We have a full 6C curriculum we call it: class, club, culture, civics, community and childhood. I’ll talk briefly about that a bit later but an early intervention in pre-literacy, we have found, is the most important gap closer. Do something at K, do pre-literacy at K by a direct instruction program off the shelf for $250, best investment you can make to bring kids to the starting line. Bring kids ready for prep.

We started our Direct Instruction journey after Multilit in 2009-2010, and we did it with the people who invented Direct Instruction. Let me talk about the elements of it because a lot of people talk about Direct Instruction, but they haven’t taken the time to really understand what it is and how sophisticated the instructional design is and the science of learning that underpins it. Everybody knows about Spelling Mastery, yes?

It is an elegant and powerful program but very few know much about other DI programs; Reading Mastery, Connecting Maths concepts, a full array of programs based on what I regard as the foundation of explicit instruction and small DI (direct instruction). First there is a placement test to place kids in their right zone of learning, and this is the one area where Vygotsky, the social constructivist and Engelmann, the direct instructionist, kind of have common ground, that is the zone of proximal development. But what DI does, it administers a placement test that very accurately places to kid, the learner, in the right zone so that the learner learns at the very next lesson, the learner experiences success in the very next lesson, not down the track. That spurs the joy and pride of having learnt something at the very next lesson because they’ve been placed correctly on the staircase. And the teacher experiences teaching success and you have got the virtuous wheels start to turn.

Secondly, clarity of communication. When Zig started this business, he understood: the clarity of communication by the teacher is so crucial. You might think all the kids got what you said, but hidden amongst those kids are the kids to whom you miscommunicated and they took the wrong meaning from what you said. So care in relation to the teaching communication was crucial in Zig’s view. The middle of your classroom seems to be getting it but there may be children in the group – if you haven’t attended to the communication properly – who are not, who are misapprehending what you tried to put across.

Third aspect: model, lead and test. This is Engelmann’s invention, or at least, articulation of what good teaching is: to model, lead, test. Anita Archer turned into: I do, we do, you do. But all of explicit instruction is derivative of the original Direct Instruction Program. The pedagogy is derivative of the old DI. The other piece, Engelmann’s theory of learning is based on the idea of presenting the children with examples, kids learn from examples and presenting those examples in the uses of rule, so the underlying design of the instruction is based on: example, example, example, rule – and then generalisation.

Once you’ve learned the rule then you’re able to generalise. John Hattie calls it: ‘surface learning, deep learning and transfer leaning.’ In my view they are the same thing. Engelmann and Carnine who designed the instructional architectural direct instruction, hammered out a set of instructional presentations that, they found at the end of it, was completely consistent with John Stuart Mill’s ‘System of Logic’. After writing this tome on theory of instruction they realised at the very end that this was completely consistent with Mill’s inductive logic in his book ‘System of Logic’.

At the most base-level: blue sky, blue car, blue bottle, blue sheep, blue blanket, blue dress my mum is wearing. What’s the rule? Blue. Present examples, introduce the rule. And of course, the alien comes through the door, the kid doesn’t know what the hell it is, but it’s blue. Example, rule, transfer, generalisation.

We brought Anita Archer out. We were the first ones to do it in 2012. We had teachers and educators from all over the country come to our conference in Cairns and when we got up to present, they all walked out! Because their system leaders had organised a kind of walkout.

A lot of our programs are based on Anita Archer’s explicit instruction.

And again, we brought John Hollingworth and Sylvia Ybarra out in 2014 and again we take a lot of guidance from them. So, the end result is that explicit teacher-led instruction is at the core of our pedagogy.

Of course, Direct Instruction is very effective. This is not only John Hattie’s finding of 0.59 as the effect size for DI. Remember this is big DI, this is not small DI. The accumulated evidence on Direct Instruction is based on the Direct Instruction program developed by Engelmann, it’s not Barack Rosenshine’s small direct instruction. The evidence based that we know of at the moment comes from big DI.

At my organisation, Good to Great Schools Australia, at first we try to urge school reform with the argument that getting the instruction right is the most important thing, and I’ve seen it play out. Immediately we introduced Direct Instruction the schools turned around. First thing you have to do with the most disadvantaged schools, you have got to turn the ship in opposite direction because it’s going south, and you need to turn the ship around. And the only way you can turn the ship around: get some learning happening. You get some learning happening if you get effective instruction. In the schools we worked in in Cape York Peninsula, you could see the ship turn and head in the right direction, because the learning process happens in the next lesson if you get it right. And you make sure that the next lesson builds on that and the next lesson builds on that.

By Easter, we felt that these schools had turned around, and it was, for first time, worthwhile to send your children there. The teachers themselves would never let their children be educated in the schools they were teaching in. They were out of there by the time their children were school-aged. They knew what a disadvantage their school was. Easter it took to go from poor to fair and the hard road that we have been on for 10 years is to break the barrier of good. But there are so many things that we have to get right. I think we’re knocking on the door of good, is what I always say to our team in Cape York, we’re knocking on the door of good. But unless we solve teacher recruitment, retention and some of these system issues that we need help on, we’re going to be knocking on the door of good for a while. I want to get to good.

We shifted from school reform because it was such a hostile place. People who want to own and defend failure, for every iteration of educational policy. They will go on ad infinitum if you let them. Our focus has shifted to curriculum and seeing how effective instruction situated in our curriculum is a better way to serve the schools we seek to partner with.

We have a comprehensive online professional learning modules to support DI. If you want to be trained in Spelling Mastery you go to the Good to Great Schools Australia’s website. If you want to be trained in any of the DI programs; we have a full suite of training available on the website and we offer it for free, all of our products will be offered for free to schools. We have a comprehensive science program F26 and what’s different about our science program compared to primary connections: it’s based on explicit instruction, we’re going to explicitly teach you science. It’s not inquiry based. We discerned from the very outset that the scientific method inquiry is different from inquiry learning.

First one good, second one bad. So we have a full F26 curriculum that we developed over the last three years, F26 science curriculum, that’s based on the explicit instruction of the ACARA science program. It’s difficult to deal with ACARA because the standards are articulated in inquiry learning terms. So you have got to have a translation. How do I teach what is assumed to be an inquiry-based approach; how do I teach this content in an explicit way? I’m very proud of our science curriculum, it is an amazing thing.

Our cross-school physics community engagement program is a musical called E = mc2 It’s the story of how Einstein put the equation together; it is a fantastic musical. There is a school in Sydney that put it on, and the Director General turned up and the guy from the ABC Science Show turned up, and we can’t even get the local guidance officer in Cooktown to come out and see it.

We have a writing program; everybody is trying to tackle writing and we are too. We have a Music for Learning program. Again, explicitly taught, highly innovative, based on the idea that the school may not have a music teacher. How do we make sure these primary schools are able to teach a proper music program even if they don’t have a music teacher? We provide a full set of resources to support the music teacher; we have a stage band. We want our kids to have a good chance of taking up the piano, taking up a brass instrument, taking up the guitar and singing in high school. If we don’t provide it to these remote schools that don’t have a music teacher on staff, you’re just basically saying ‘Nah, that’s not for you.’ So we have a Music for Learning program. I’m working with a team on a program called Lightning Maths that is supplementary to the main DI program, aimed at automaticity and the four operations and 400 number facts. I’ve got onto this American program and I can teach a child in 20 minutes a times table, never to be forgotten. So this holds out the promise that we can teach the full multiplication and division tables in very short order, utilising the Making Maths Real program from the United States. We’re thinking we have a base maths program but we want to supplement it with a Lightning Maths program because the multiplication tables are so crucial to algebra in early High School; complete automaticity and the full sense of numbers that you need in order to succeed in algebra, is what we’re focusing on.

Finally, a WordAttack/WordPower supplementary program. I told Jennifer Buckingham that I’m a bit obsessed with syllables. I think it’s a missing piece; I’m not sure if she agrees with me. We have a small 15-minute intervention to bridge phonics and phonemic awareness with word cognition and we are going to trial that in our schools. This is entirely personal prejudice because it was the way I learned. Per-pen-di-cu-lar. When the school inspector came to my school when I was in grade 4, he said, ‘What are the words that you know?’ and I said, ‘Vo-ca-bu-la-ry,’ and he said, ‘Yes, you said it with all the syllables.’ It is entirely the way I know how to pronounce things and speak and spell and the entire acquisition of a vocabulary requires those things: pronunciation, spelling and meaning. We glue those three things together and you’ve added another sight word. Never again will I need to sound out per-pen-di-cu-lar.

Finally, John Hattie’s Visible Learning. This quote I always come back to. Every year I present lectures to teacher education students and find that they are already indoctrinated with the mantra ‘constructivism good, direct instruction bad.’ It’s worth reading the chapter on Direct Instruction from Hattie.

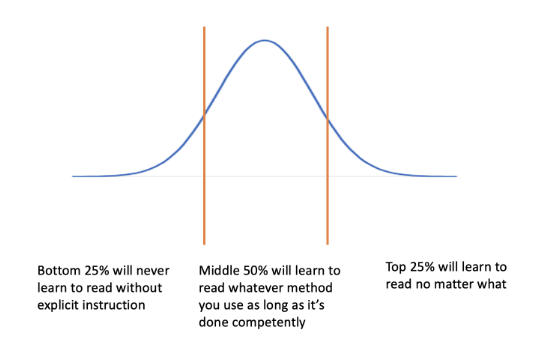

One argument for explicit instruction and literacy is Kevin Wheldall’s argument: bottom 25 per cent will never learn to read without explicit instruction, middle will learn to read if you do it competently, and the top 25 per cent will learn to read no matter what. That’s Kevin’s rule of thumb and you see it play out in the classrooms, in the data. This is a quote from Hattie: ‘Does it work for all students?’ My metaphor is ‘Does Johnathan Thurston need ball practice?’ Well my answer is, ‘It won’t hurt him.’ So even the kids who would have got through anyway benefit from explicit instruction. The top 25 you might say: ‘They really didn’t need that.’ Fluency and practice, they’re all good things.

This is Wheldall’s rule, the bottom 25 per cent will never learn to read without explicit instruction. Of course, the argument for explicit instruction applies even more to numeracy. It’s not 25-50-25; failure in mathematics is much greater.

Another argument for explicit instruction is that the phonemes of Aboriginal languages and other non-ESL students often are at odds with English.

On this side are phonemes of my language and phonemes of English that don’t have an equivalent in our language. If you don’t give the kids explicit instruction in these phonemes, they are going to be behind everybody else. Phonemic awareness is just so crucial and it won’t just be picked up implicitly.

Third argument is that word exposure is low in SES homes. Risley and Hart’s findings about the ‘word gap’ between middle class kids and kids from working and underclass families.

Fourth argument is limited exposure to books in low SES homes and another argument is poor parental literacy.

If you want to do social justice, you have to address these arguments. If you are careless about it and you think ‘Oh well, the middle-class kids got through,’ then you can maintain course, I suppose. But if you want to make sure that the most disadvantaged kids in the class have a chance too, then we have to address the fact that they need explicit instruction.

The theory of learning that underpins direct construction is induction, as I said, based on the learners’ capacity to discern similarities, differences and other patterns from the example. In fact, the proper DI ways is not to expose the kids to the rule at first, but to expose the examples first, because the learning brain is able to discern the rule and use the rule.

I just want to say where this ideological battle comes from, I want to close out on that. I think the origins of this tragic discourse between implicit and explicit instruction in education has a rather benign beginning; this is my theory anyway. I’ve seen it play out, I’ve seen this discourse playout in other fields: native title, welfare reform. All areas of policy, I can see the origins of the ideological battle. And it is this, in my view, the discourse becomes ideological because you get two views forming about something.

One camp says: ‘What is this? This is tails,’ and the other camp says: ‘What is this? This is heads.’ Then they get stuck in their view, and then interests come to bear in holding those views, and the synthesis of the view in relation to this analogy here is that it is a coin. Yes, tails is half right, and heads is half right, it’s just that we’re seeing it in different ways, from a different perspectives, and if we don’t realise that these things are closer together than we think, then the ideological discourse heats up and, as I say, interests come to bear on which position you take.

I think that has happened with the argument between implicit and explicit instruction in education. So you have got the implicit learning crew on one side, discovery learning, child-centred learning, and social construction. Social construction is not wrong in the natural development of children in society. Of course, Vygotsky, king of the social construction and zone of proximal development, argues about creativity and critical, problem-solving skills and so on, and on the other side, our crew, who are in the explicit instruction, direct instruction, teacher-led instruction, placement testing, content knowledge, memorisation. I think there is a way of synthesising this conflict. I believe that there is a relevance to implicit learning, but this is relevant to biologically primary knowledge; kids learning naturally learn that way through social construction. Of course, with placement testing, as I said earlier, both Vygotsky and Engelmann are onto it, onto the zone of proximal development.

The other synthesis is that this is what school education is all about; school education is about explicit instruction, not implicit. It’s about direct instruction, not indirect, and it’s about teacher-led instruction rather than student-led inquiry, and this is about the acquisition of what Dewey calls Biologically Secondary Knowledge. Of course, the point about creativity and critique and content knowledge, creativity and critique comes from knowledge. Ross and I have this huge affection for John Milton. As John Milton, you can’t write the greatest piece of literature the world has ever seen unless you spend a long time filling the wells of knowledge. The guy was 55 before he started. You just cannot produce a work of such stupendous creativity without having first filled up the tank with vast reading.

Summary is: in our social and cultural lives, from the time we are born, we learn from play, from discovery, from inquiry, from implicit learning, and we learn from and imitate others, that’s in our social and cultural lives. But we’re at school now, and in school, we learn that being taught by someone who knows more than we do is what it’s all about. It’s about learning from the teacher, and we learn a lot from reading and imitating someone who knows what we don’t know. That is my attempt to try and synthesise that discourse between implicit and explicit teaching and learning.

I just think that the other mob have got it wrong about their understanding of how children learn and what we should do with the kids based on that understanding. I think they should be talking about what happens at home and down the creek, at Bunnings or whatever. Living life is how you learn implicitly. But school is a different place, where we have deliberately decided what we want kids to learn, and we’ve decided that the teacher is the one with the knowledge who can teach those kids.

Thank you.