On Wednesday, June 19, 2024, Noel Pearson presented a compelling webinar on Direct Instruction. Hosted by McGraw Hill Australia in collaboration with Good to Great Schools Australia (GGSA), the event was titled The Power of Direct Instruction and featured insights from GGSA’s founder and director, Noel Pearson. If you’re interested, members can view the webinar recording or register for a free membership to access it here.

In this article, we provide a short overview of each section of the webinar:

- Introduction

- Origins of Direct Instruction

- High-Level Points about Direct Instruction

- Introducing Direct Instruction in Cape York

- Instructional Design of Direct Instruction

- Good to Great Schools Australia

Introduction

Noel Pearson commences the webinar from Cairns, the headquarters of Good to Great Schools Australia, stating that the session revolves around ‘a favourite subject’ of his – Direct Instruction (DI). Pearson shares his journey, recounting his origins from a humble family in Cape York and his early education at a modest primary school in his hometown of Hope Vale. His academic path led him to St Peters, a Lutheran college in Brisbane for high school, where he studied as a boarder, and subsequently to The University of Sydney, where he studied history and law.

Reflecting on his experiences, Pearson expresses, ‘I’ve been all too conscious throughout my life that, from a very poor family – that nevertheless gave me great blessings I’ve had through the education my parents encouraged me in – huge life opportunities opened up, and I’m just so passionate about young people from my community having the same opportunities that I’ve had.’

Pearson emphasises that education is pivotal for the advancement of his people in Cape York and essential for closing the gap, a process that he contends must start in primary school. ‘The achievement gap between the children who leave our remote schools is up to five to six years behind the mainstream, so when our children turn up in Cairns, or Brisbane or Townsville, they find themselves with peers who are many years ahead of them, and this, of course, drives loneliness, disappointment and children dropping out because we didn’t furnish them with the education they needed to succeed.’

He concludes the introduction by stating that the focus of the webinar, titled The Power of Direct Instruction, centres on a program he deems vital for reforming primary education for all students and particularly for disadvantaged children. Pearson passionately advocates that Direct Instruction is the solution to equip children with the education necessary to thrive, thereby closing the educational gap and fostering equality.

Origin of Direct Instruction

Pearson opens the discussion by introducing Siegfried Engelmann, the visionary behind Direct Instruction, detailing how this young advertising executive made a radical career shift. Driven by a compelling curiosity to determine how many repetitions an advertising slogan needed to be ingrained in a child’s mind, Engelmann’s journey took an unexpected turn. ‘He immediately dropped his career in advertising and turned to education; he was so fascinated by what he’d started to do with the children, and the whole question of how it was, and how it is, that human learners take information and learn knowledge that becomes embedded in their long-term memory,’ Pearson shares.

Pearson proceeds to unpack the insights Engelmann and his colleagues gained while empirically investigating the question: ‘How many exposures were needed before children converted short-term memory to long-term memory?’ This inquiry laid the groundwork for their pioneering work.

Moving forward, Pearson discusses the initial Direct Instruction programs (DISTAR) developed by Engelmann and his team, highlighting how these programs evolved to enhance the clarity and sequencing of teaching methods. He emphasises the inclusive aim of DI, which is designed to ensure no learner is left behind.

‘This bottom 25 [per cent of students] is made up of children from homes without books, illiterate parents, low socioeconomic circumstances, learning difficulties,’ said Pearson. ‘All of these kids are susceptible to being part of the bottom cohort, and the crucial thing for them is for them to receive explicit and direct instruction in literacy. For me, the 25/50/25 classroom is the most crucial driving policy insight; this is the insight that drives all of my convictions – because I’m concerned about the bottom 25. They’re kids I’m worried about. I’m worried about all of the kids, but I want to put an end to the bottom 25 missing out all the time and us putting it down to them when they can’t read and when they end up not finishing Year 12,’ Pearson passionately explains.

Pearson then transitions to an overview of Project Follow Through, the most extensive educational experiment ever conducted. This initiative sought to address the question of how primary education in the United States could be reformed to ensure equal opportunities in the post-civil rights era. Pearson laments the missed opportunity, noting that despite Direct Instruction being identified as the most effective method for teaching reading and writing, the failure to implement these findings was a grave injustice. This neglect, he argues, has perpetuated the unfulfilled promise of citizenship for African Americans and the continued deprivation of quality education for their children.

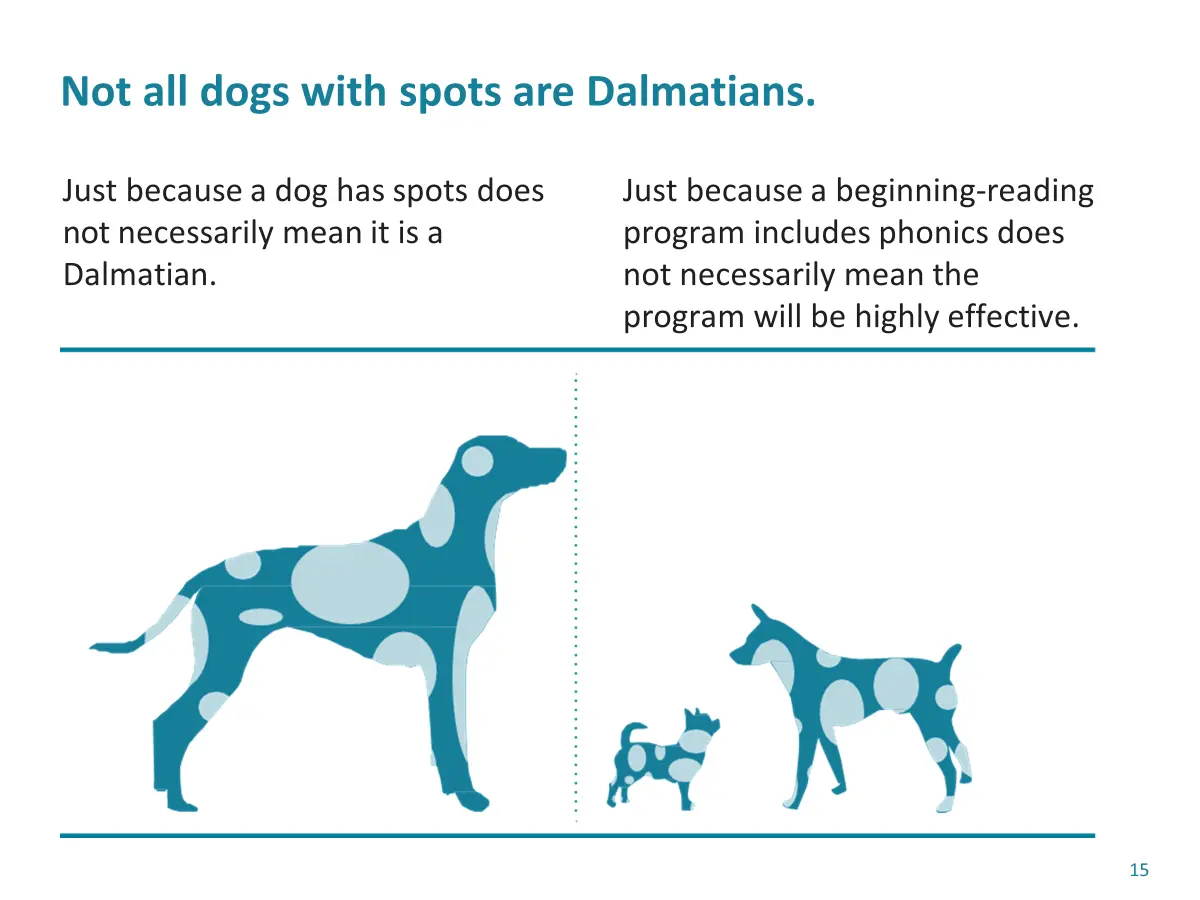

Pearson then explores the features that render Direct Instruction an exceptionally effective program. He cites Engelmann’s analogy, Not all dogs with spots are Dalmatians, to illustrate that not all beginning reading programs with phonics are highly effective. Pearson then swiftly reviews the axioms of DI outlined in Engelmann and Geoff Colvin’s 2006 book, Rubric for Identifying Authentic Direct Instruction Programs. These axioms are particularly useful for anyone considering developing their own program and encompass elements such as the presentation of information, task structuring, task chaining and the design of exercises.

High Level Points about Direct Instruction

Pearson begins the next section – High-Level Points about DI – by listing 12 points that make Direct Instruction ‘simply good teaching’.

- Aim instruction at every learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

- All lessons respect Cognitive Load.

- Systematic spaced practice.

- Accurate formative testing through placement tests.

- Model, lead, test (I Do, We Do, You Do).

- Mastery learning.

- Mastery tests.

- Inclusive learning.

- Avoid expertise reversal.

- Carefully designed logical learning sequences.

- Concise, carefully worded communication.

Pearson then reflects on renowned advocates of explicit instruction, Barak Rosenshine and Anita Archer, pointing out that their adherents often overlook the fact that the principles and paradigms they espouse are essentially derived from Direct Instruction. Rosenshine’s well-known Principles of Instruction closely mirror the instructional design of the pioneering DI programs, specifically DISTAR. ‘I just wanted to make that point, that with the current enthusiasm, correct enthusiasm by the way, about Rosenshine, the important thing to know is DI preceded Rosenshine. This is another point, given the growth in enthusiasm, again quite rightly, for explicit instruction, it’s important to understand that explicit instruction’s central pedagogical paradigm – I Do, We Do, You Do – is a derivative of Direct Instruction,’ Pearson continued.

Pearson explains that Anita Archer, a leading proponent of explicit instruction, had a strong association with the DI community when Good to Great Schools Australia engaged her for teacher professional development in 2012. ‘There’s some lack of recognition by people who are enthusiastic about explicit instruction that that paradigm was actually hammered out by the DI people in the 1960s. It was called modelling (by the teacher) and then leading (the teacher leading the group) and then testing (testing you as a learner and independent practice),’ said Pearson. ‘This is a point that I came to recognise myself because I was familiar with all of these traditions and I could see that one was the child. Explicit instruction is really the offspring of Direct Instruction, but like a lot of offspring, sometimes the parent doesn’t own the progeny and the progeny doesn’t own the parent. But I can see very clearly the fact that explicit instruction is in fact derivative of Direct Instruction, at least in relation to that paradigm,’ he continued.

Pearson then explores how DI includes both massed practice and deliberately scheduled spaced practice to combat the curve of forgetting, all while incrementally building knowledge and skills towards big conceptual ideas. ‘The design of the program is not just about the next increment, it’s not just the next step, the next task. The program is designed to get you toward the big vista, the big concept, the big ideas. All of these steps are building a big picture and connecting big concepts together for you,’ explained Pearson. ‘So, DI is this fascinating strategy for building conceptual knowledge through incremental steps, so that the learner at the end of the sequence, all of a sudden, sees the big picture clearly. The program is very deliberately constructed so that concepts, the big ideas underpinning the concepts, the big picture, the gestalt, come together,’ he admired.

Pearson further points out that Direct Instruction agrees with two highly influential concepts in educational psychology: the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and Cognitive Load Theory. ‘Can you believe that?” he asked in astonishment. “This is the coming together of Direct Instruction, Engelmann, with the great constructivist, Lev Vygotsky. And Zig actually wrote in 2015 an article on his site called Teaching within the Zone of Proximal Development. DI is all about the ZPD,’ Pearson highlighted. This intersection signifies a convergence of Engelmann’s Direct Instruction with Vygotsky’s constructivist approach, underscoring DI’s depth and adaptability.

Pearson also underscores that DI responded to cognitive load before John Sweller and his colleagues developed Cognitive Load Theory. ‘Cognitive Load Theory arose in the 1980s and, of course, very thankfully and very powerfully, is now a part of the education conversation right across this world. Right across the world this theory, Cognitive Load Theory, by this Australian professor, Sweller, has had a tectonic impact on education approaches across the world. But as I said earlier, DI responded to cognitive load long before cognitive load was discovered, was developed, and that was because Engelmann focused on the brain and studied very carefully the teaching input and the learning performance that resulted from the teacher teaching,’ said Pearson. The attention to cognitive load exemplifies Engelmann’s forward-thinking approach and the robustness of Direct Instruction as an educational program.

Finally, Pearson begins a discussion on maintaining high expectations for students, illustrated by a picture bearing the words ‘If the student has not learned, the teacher has not taught’ etched in stone. ‘Reflecting this principle that all students can learn, this is Zig’s operating principle, this is the operating principle of Direct Instruction,’ he explained. ‘There are no alibis here, guys. If the student has not learned, the teacher has not taught. We do not blame the learner; we do not blame the child,’ he said. ‘We have high expectations of the child, but if we hold these expectations, we must provide the necessary teaching to help them meet those standards. High expectations cannot be just a mantra or a geeing up of the troops; it can’t just be some kind of empty form of encouragement. High expectations mean we have a responsibility to give the children the means to meet those expectations. And how do we do that? This aphorism tells us: if the student doesn’t learn, then we have not taught,’ said Pearson.

Introducing Direct Instruction in Cape York

Pearson kicks off this segment with a video chronicling Layne’s reading journey, starting as a Prep student at the Cape York Aboriginal Australian Academy and progressing to a boarder at a private school in Charters Towers. ‘This is my favourite learner from Cape York, called Layne,’ he says.

Pearson then recounts the inception of the Direct Instruction initiative by Good to Great Schools Australia. Engaging in the mid-2000s’ reading wars debate, he and the GGSA team were influenced by the National Reading Panel’s reports from 2005 and 2009. Their advocacy for educational reform in Cape York culminated in the publication of a report The Most Important Reform, calling for radical change. In 2009, Pearson and the GGSA team visited numerous charter and DI schools across North America, particularly those in African American communities. They had the opportunity to meet Engelmann and his team at the National Institute for Direct Instruction in Eugene, Oregon. This visit solidified their resolve to implement DI in Cape York.

As a result of what was learned in the 2000s, Good to Great Schools Australia established the Cape York Aboriginal Australian Academy in two schools in Coen and Aurukun, which currently operates in Coen and Hope Vale. The Academy offers a comprehensive curriculum known as the 6C program, encompassing Class, Club, Culture, Childhood, Civics and Community. The Class program is based on Direct Instruction for English and maths and explicit instruction for subjects lacking a DI program, such as science, music and ancestral language. Pearson emphasises that the Academy offers ‘a full curriculum, but DI is the backbone of our curriculum.’

Pearson vividly recounts the astonishing transformation he witnessed at Aurukun school, describing it as one of the most extraordinary things he has seen in his life. ‘It was a hell of a ride,’ he remarked. ‘We had not much more than a month by the time we got permission from the Queensland Education Department to start at the beginning of 2010. It was a very chaotic beginning, and it was one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever witnessed – the sheer chaos and difficulty,’ he said.

‘These schools were in a very bad shape,’ he explained. ‘The children were not used to much more than having a DVD put on the television set as a child-minding strategy, in between walking on the roof of the school and walking out of the classrooms at their own behest,’ he continued. ‘We had 60 kids at one time in the time-out room and we thought there was a cyclone blazing. But the Direct Instruction program brought a logic; gave the school a logic. All of a sudden, everybody knew what to do, it was like a machine had started to crank up and the logic of learning had started,’ he explained.

‘That’s the thing about effective teaching, that’s the thing about DI,’ he asserted. ‘You learn something in the next lesson – not next week, not next month, not after a while – you learn in the next lesson. You experience that little tinge of success and excitement because the learning has been pitched right in front of your nose and you’ve succeeded, and that excitement transfers to the teacher, because not only has the learner experienced learning success, the teacher is feeling teaching success. This creates a virtuous wheel starting to spin between the teacher and the student. You succeeded with that last lesson and guess what? We’re moving on to the next one and you’re gonna succeed with this as well. You’re not gonna feel like a failure. You’re not gonna feel like somebody’s trying to teach you Greek,’ he said.

‘And this virtuous wheel starts to turn in every classroom,’ he continued with enthusiasm. ‘But the core of it is between the teacher and each of the students and then the classroom starts to hum. And then all the classrooms started to hum, and by Easter, we had a coherent school. The time-out room went from 60 down to four or five. And five o’clock on a Friday afternoon the kids were still doing their lessons. It was just one of the most extraordinary things I’ve seen – a poor school, completely dysfunctional, completely chaotic, completely without purpose, without logic, and yet when you get the instruction right, the school comes right,’ he concluded.

Pearson then invited the audience to explore a pivotal publication from Good to Great Schools Australia titled ‘Effective Instruction: The keystone to school reform’, which was published in 2013. ‘Every galah in every pet shop is talking about explicit instruction nowadays and phonics and direct instruction and cognitive load and everything else,’ he remarked. ‘Well, we were talking about it in 2013. It’s all in this publication: ‘The keystone to school reform’. The keystone being: think of building an archway, the most crucial stone in the archway is the stone in the middle at the top, which holds the whole structure of the archway in place. What is that stone? The stone is effective instruction. You can’t build an archway to education if you don’t have effective instruction at the very apex of your school.’

Download Effective Instruction: The keystone to school reform here.

Pearson then showcased clips of Direct Instruction being implemented in classrooms at Cape York Aboriginal Australian Academy. Although time limitations prevented the entire video from being shown, it is available for viewing below.

Instructional Design of Direct Instruction

In this section, Pearson unpacks the instructional design, or the hidden architecture, of Direct Instruction. He outlines five pivotal features that underpin this approach:

- formative testing through placement tests

- model, lead, test

- presentation of examples, followed by rules, leading to generalisation

- spaced practice

- mastery learning

- learning tracks.

Pearson starts by explaining the importance of formative testing and placing learners where they can succeed. ‘This is so that the very next lesson is within the zone of each learner,’ said Pearson. ‘We’re not gonna come around to something you understand some time down the track. No. Tomorrow the learning is going to be in front of your nose and you’re going to be able to succeed,’ he asserts. ‘How we do that is we have a very ingenious system of placement tests built into the program that enables students to be placed at their correct spot in the program,’ he said.

Following this, Pearson discusses the model, lead, test cycle, highlighting how it happens in a very short cycle within Direct Instruction, differentiating DI from other explicit instructional methodologies. ‘This paradigm occurs in very brief cycles, a constant rhythm in the way DI material is presented,’ said Pearson.

Pearson then turns his attention to the concept of examples, rule and generalisation, describing it as ‘the essence of DI,’ though not well understood. ‘One aspect of DI that is often misunderstood is its central learning strategy: the presentation of examples. These examples generate a rule, which can then be generalised. This principle is the essence of DI,’ he states. ‘Present examples that lead to an inference, distil the rule that underpins all these examples and then enable the rule to be generalised to new, novel examples. Engelmann and his colleagues emphasise the importance of examples, rules and generalisation. In a book about teaching science [Visible Learning for Science], [John] Hattie and his colleagues discuss surface, deep and transfer learning, which parallels the example-rule-generalisation model,’ Pearson adds.

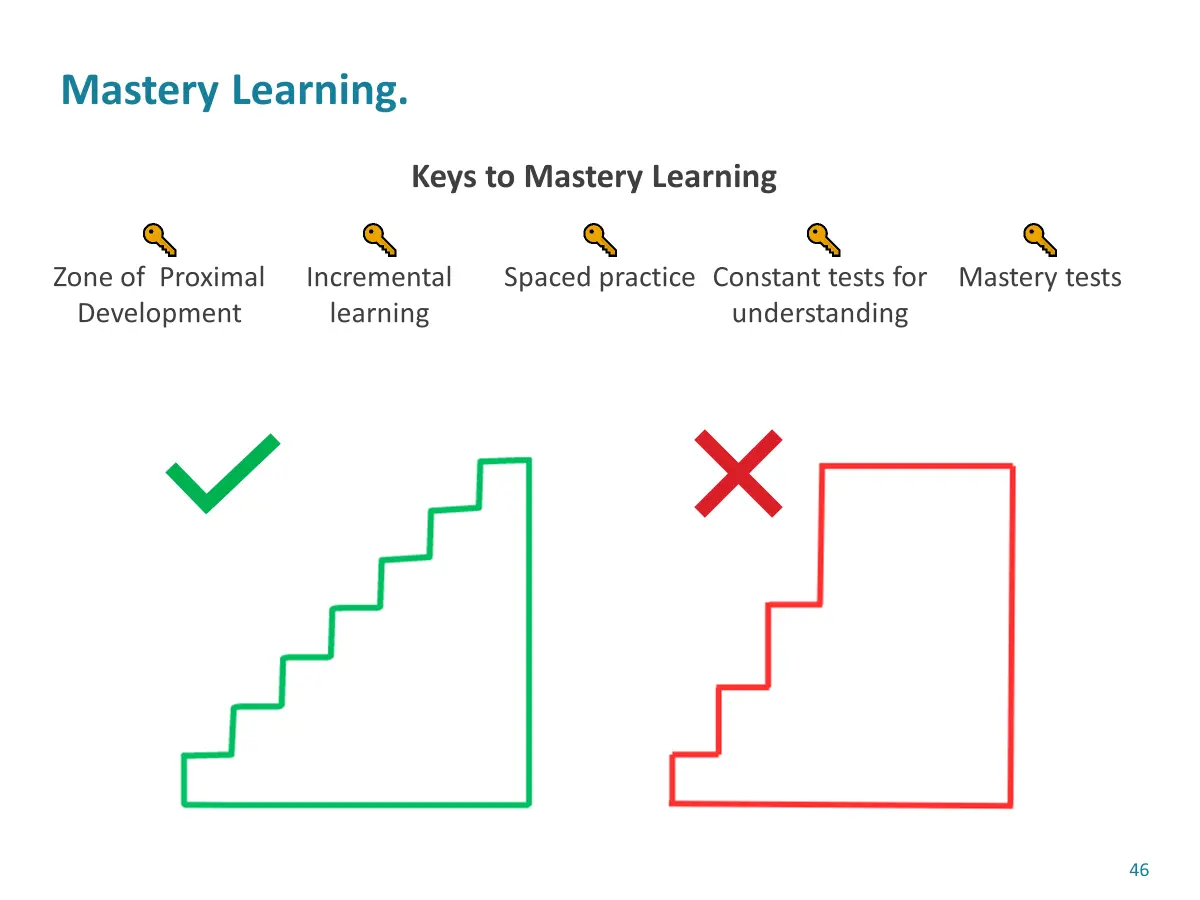

Next, Pearson explores spaced practice and mastery learning, presenting them as integral components of Direct Instruction. Mastery learning involves several key elements:

- the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

- incremental learning

- spaced practice

- continuous testing for understanding

- mastery tests.

Using the image below, Pearson explains how mastery learning facilitates learner achievement by progressing in small, manageable steps. ‘This little image is an explication of what DI aims to do. Every step is a constant step upward, there’s not a step that is inordinately hard to get over, everything has been designed so that the next step is as easy or as difficult as the previous step. It’s a crucial part of mastery learning that the increments of learning are very evenly spaced,’ Pearson explains.

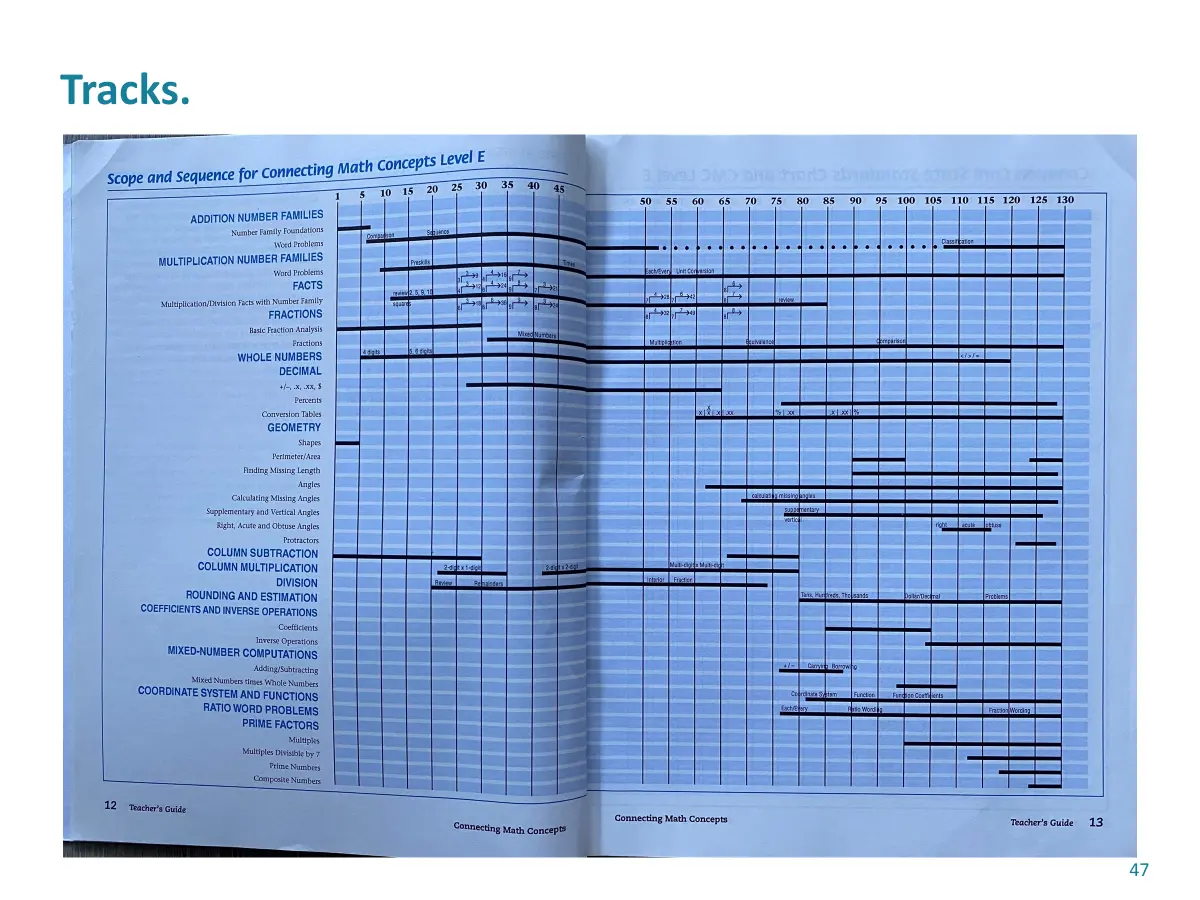

Pearson subsequently addresses the concept of tracks in DI, portraying them as the solution to the challenge of maintaining student engagement over a 45-minute class focused on a single subject. ‘The idea is that learners disengage after 12 minutes; this was an empirical, cognitive finding based on the performance of learners [in Engelmann’s research]. Tracks is an unrecognised aspect of DI programs, and the challenge for explicit instruction is, how can you maintain the focus of children for 45 minutes on one subject and the load that’s involved with that? Well, tracks represents the antidote to that problem, so you’re not losing learners along the way, you’re switching to the next exercise,’ Pearson concludes.

Good to Great Schools Australia

In this segment, Pearson outlines the work of his organisation, Good to Great Schools Australia, in supporting schools around the nation to implement Direct Instruction effectively. He describes how GGSA maps DI programs to the Australian Curriculum and develops resources to enable schools to deliver DI in complete alignment with the Australian Curriculum. ‘In our work at Good to Great Schools Australia, we have mapped the DI programs against the Australian curriculum,’ he said. ‘The other thing we have developed is Swap Outs and Top Ups to meet the Australian Curriculum. We swap out the American dollars and the other Americanisms in the DI programs, producing Australian replacements for all of the Americanisms in these programs. Our team of curriculum developers and writers produces these swap outs and they’re completely consistent with the DI format,’ he said. ‘But also those areas of the Australian Curriculum with the DI programs there might be something missing from the DI programs that are required by the Australian Curriculum. Well, we produced top ups to fill those gaps,’ he continued.

You can view our mapping resources here.

Pearson then shifted focus to Good to Great Schools Australia’s online professional learning modules, designed to enhance the skills and knowledge necessary for the effective delivery of DI programs. ‘We have professional learning resources for teachers online. These are freely available, on how to deliver and implement Direct Instruction. And teachers can access professional learning resources on our website. And all of our resources are free to schools,’ he highlighted.

You can see Good to Great Schools Australia’s full suite of professional learning modules and Top Ups and Swap Outs, to support the delivery of Direct Instruction here.

Pearson then described Good to Great Schools Australia’s ongoing commitment to enhancing educational outcomes, by providing comprehensive implementation, support and coaching services for schools nationwide to facilitate the adoption of explicit and direct instruction programs. ‘And we’ve been doing that for 15 years. We have sites all over the country,’ he said.

Pearson next turned his attention to the policy, system improvement and school improvement initiatives of Good to Great Schools Australia. ‘We think a lot about and do a lot of policy work, as well on school improvement,’ he said. ‘We have this document: ‘Eight Cycles of School Practice’, which is a handbook for how a principal and a faculty of teachers can grab a hold of their school and implement these eight cycles of school practice to get the wheel turning… so that you have effective instruction start to drive, a humming school,’ he continued.

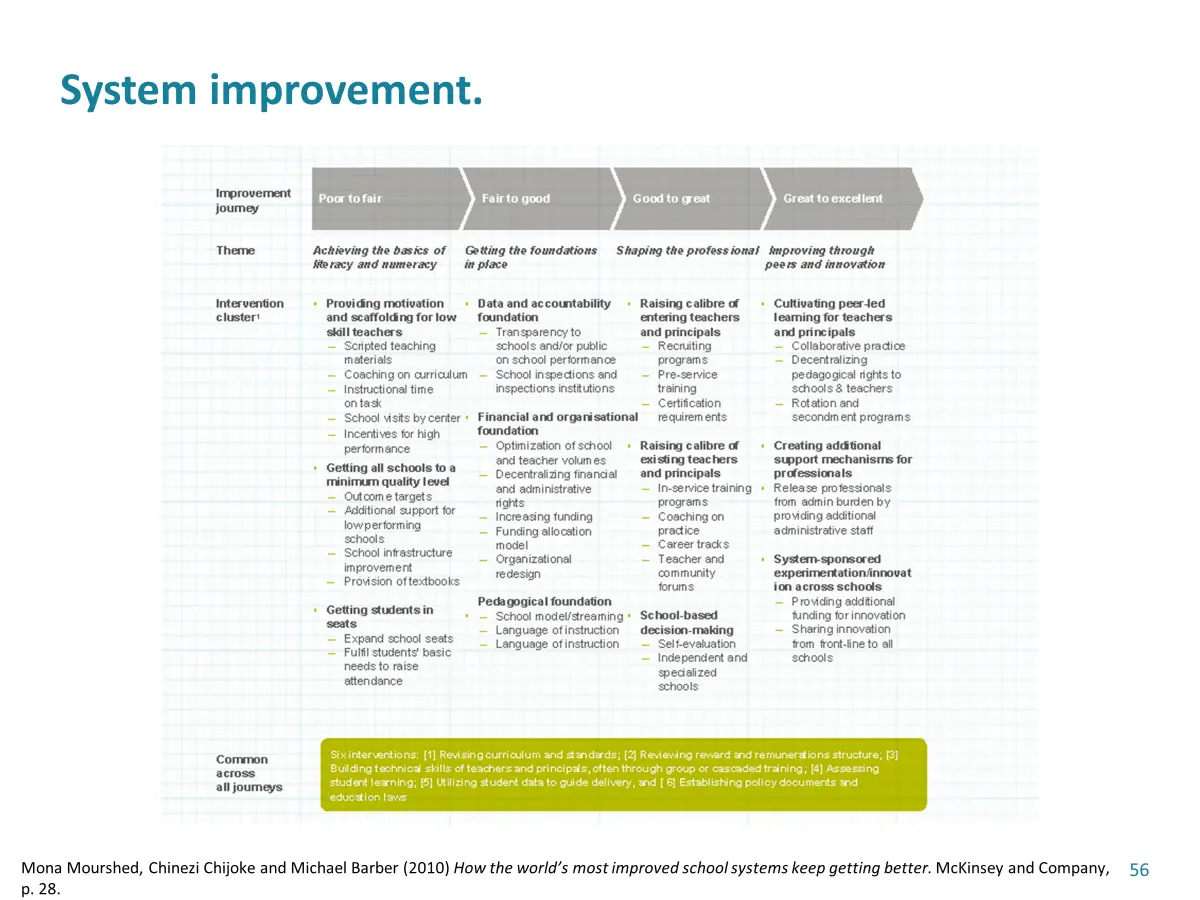

Pearson then emphasised the critical importance of system improvement. ‘This is completely galvanising to us,’ he said. ‘This is taken from McKinsey and Company’s 2010 report on How the Best Systems in the World Improved… and they came up with three ingredients. Put the right teachers in place was the number one. The teaching, two. They have to deliver effective instruction. And three, every child must benefit. Every child in the system. Those systems around the world that have been outperforming us in Australia; they get three things right, according to McKinsey (2007). The right teachers deliver effective instruction, benefiting every child,’ said Noel.

‘What do you do to travel though these different parts of the performance spectrum? There seems to be a commonality. If you’re in a poor school, you need to do this to get to fair. If you’re a good school and you want to get to great, you need to do this. The formula is a bit different. I tell you what is universal across all the performance spectrum. What is universal is effective instruction. That is the one thing you have to do at all performance stages. You have to focus on effective instruction,’ said Noel.

Pearson focused particularly on schools classified as poor within the McKinsey performance spectrum, representing the lowest-performing institutions. ‘’With poor schools, you’ve got to turn them around. Poor schools are heading somewhere south. You have to turn the ship around and head north. There is a struggle with our most poor performing schools, our most disadvantaged schools; they’ve actually pointed in the wrong direction. And you’ve got to turn the screws so that it turns in the right direction. That part is the challenge… and we do that by improving our instruction according to international evidence,’ he said.

Turning to the membership of Good to Great Schools Australia, Pearson highlighted the resources and professional development opportunities available. ‘Our members, using our Direct Instruction resources and professional development resources and explicit instruction resources, are drawn from public, independent and Catholic schools across Australia. Approximately 1500 schools across the country access our resources, including a sizable number in all of the jurisdictions. We offer them for free. If your school signs up to be a resource partner and your principal signs to be a member, then your entire school faculty has access to our resources,’ Pearson said.

Pearson's Secret to Closing the Gap

Pearson wrapped up the webinar by unveiling his secret formula for closing the gap – preventing the gap before it begins. ‘I’m going to tell you about a secret to closing the achievement gap by the beginning of primary schooling,’ he said. ‘The gap for the migrant kids, the gap for the poor white kids. You know how many poor white kids are missing out on a good education? They’re moderate, but they don’t read well, fluently, there’s too many limitations. This is my one secret. If I’ve learned anything that I’m absolutely convicted about is that you close the gap in the beginning,’ he declared.

‘You close the gap so that by the time they start they’re at the starting line. They’re lining up for the 800-metre race. You don’t want to start 800 metres behind, or 50 metres behind everybody else, or 200 metres behind. You want them at the line. Well, this is the way to get them at the line. You close the achievement gap through 20 minutes a day in pre-primary school pre-literacy education. These are the two programs. McGraw-Hill might set you back 250 bucks for this. You teach a whole class with 250 bucks? Teach a whole school. These are the two programs. Master the first 30 lessons of Language for Learning, an SRA program, an early generation DI program, and mastery up to lesson 40 of Reading Mastery Language. Twenty minutes a day for kids in kindergarten. If you do this 20 minutes a day, they will turn up in Prep fully at the starting line. And at the starting line, they’ll actually be ahead of kids in mainstream schools; they could be more prepared than the average kid at a mainstream school. If you can get kids in kindergarten to do 20 minutes a day, they can do the play program for all of the other minutes of the day. These 20 minutes are the most crucial,’ he explained.

‘We’ve seen too many instances of miracles with young learners all of a sudden, from non-English speaking backgrounds, no books in the home, parents who can’t read and write, living in poverty. I’ve seen these kids. When they’re given this power here, all of a sudden you’ve got the means for them to start. No gap opens up. The best gap is the gap that never starts. We don’t have to solve every socio-economic problem in the world. If we solve this, we give the child the ability,’ he continued.

He concluded by sharing his aspirations for Layne, the young student who started her reading journey through Direct Instruction at Cape York Aboriginal Australian Academy. ‘Young Layne, the hopes I have are high right now. She’s at boarding school in Charters Towers Catholic College. I have absolutely no doubt she’s going to year 12. And she’s going to go beyond. All because she was given access to this. This is the secret to closing the achievement gap. So that every child is able to start at the starting line.’ he concluded.

Q and A

Although time was running out for the question and answer session at the end, we did get to put one audience question to Pearson. The rest of the questions that did not have time to be addressed have been provided to Pearson and will be added to this article as soon as possible.

Q. ‘This is a statement more than a question. I just don’t understand why we are not all using DI in our classrooms, or at least in our intervention. I suspect it is the law of autonomy. Do you have any thoughts on that, Noel? Why is DI not more widely used?’

A: ‘We gotta work out who the priority here is. Is it the child? Who was it? The adults. And the priority is the learner. And there are just countless people who come to our schools quite, sometimes hostile. But we have only one request of them to say, give it a chance. See for yourself the effect that it has on the child’s learning and come to a judgment sometime down the track. And in all of the cases, in all of the cases, which teacher is not going to be persuaded by the performance of their children, of the students? In all of those cases, people with scepticism and so on, people with ideas about teacher autonomy and everything else, they understand that the program actually builds. I mean, I’ve seen some magical teaching come from kids, you know, young people who’ve been fresh out of university by the time that they teach in Cape York. And this is our big problem. By the time they leave Cape York and they go down to, you know, Sunshine Coast or Gold Coast or Brisbane or wherever, they are absolutely extraordinary teachers. Then, because of their experience with us in the Cape, they’ve actually learned, all of it; they’ve become very mature teachers. And, so I just say to everyone, it’s the performance of the children that will persuade you and the fact that there is no greater delight and no greater sense of esteem that a child can have than to be successful. And the key priority we have as educators is to give the children the means to be successful.’

View Good to Great Schools Australia's resources to support the delivery of Direct Instruction in Australian schools.

Review our free mapping, swap outs and top ups and professional learning modules.